- Home

- Jakuta Alikavazovic

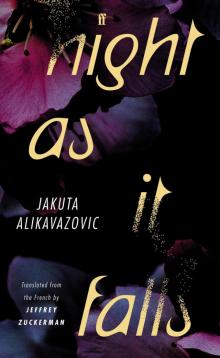

Night as It Falls

Night as It Falls Read online

JAKUTA ALIKAVAZOVIC

Night as It Falls

Translated from the French by

Jeffrey Zuckerman

Contents

Title Page

hotel nights

it’s complicated

night as it falls

Author’s Acknowledgements

Translator’s Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Paul was with Sylvia when he found out what happened to Amelia Dehr. In bed with Sylvia, who was sleeping, or pretending to, as blurred glimmers from outside, from the bateaux-mouches, bathed them, sweeping nonchalantly over their bodies, across the sheets, up to the ceiling. He mulled over how they might just blend into the space, into the surroundings, and maybe that was happiness, or the closest thing to it. Camouflage, really, Paul thought.

There was a phone call, she was between life and death, and Paul knew there could only be one outcome. Amelia Dehr wasn’t the sort to hold back. This precarity, rather, betrayed just how fragile, how frail she now felt – must have felt – not in going through with it but rather in failing, with an imprecision wholly unlike her. An imprecision that convinced Paul that at the moment she had set to ending it all, she was no longer the woman she had been. She had ceased to be Amelia Dehr.

The other possibility or interpretation – the idea that something in her was clinging to life, refusing to die; that the true Amelia Dehr, the one he had known, loved, yearned for, hated, this Amelia Dehr was now battling against death; the idea she was on the losing side, and was losing everything – was unbearable to Paul. He would rather believe that for ages now the woman about to die, the one struggling, had not been the real Amelia Dehr, that the relationship she bore to Amelia Dehr was the shaky one connecting a leaf to the tree from which it had fallen.

She had sunk into insanity, Paul thought, she who at twenty had been resplendent, lively, wildly imaginative; she who, lying in the grass, seemed to be an extension of the grass, no, even more than that: its continuation, its tenderness – she who, lying in the grass, seemed to be the wisdom of the grass, its vivid essence. The last time he saw her, he had been shocked to see her unkempt. Worse than that; listless. Lacklustre, even. She was sure she was being watched. She had called him and asked him to come meet her in the courtyard. She trusted him to tell her; as he stood down there, could he see her at her desk? He hadn’t understood the question. He would rather not have understood, had been tempted to brush it aside. Out of tact, or cowardliness. Or a tact that was also cowardliness. Why don’t you go back up, he said, that’d be easier, that way I can tell you whether you can be seen. Or not. The look she gave him wasn’t blind, strictly speaking, not so much blind as unseeing. It was a gaze that simply took him in amongst other things. As if Paul himself were somewhere beyond his body. And he felt himself drifting away. His spirit or personality or soul was just floating off, away, towards this place where he wasn’t, couldn’t be, but where Amelia Dehr’s gaze fell. This was the kind of power she still held over him. She had clutched his hand and, in a rush, before her pride (because she had been so proud, it was so much a part of her) forced her to hold back her words, she had let out: No, I want you to tell me if I’m sitting there right now, you have to tell me, Paul, please.

She was one of those people who destroyed everything and called it art.

*

At that time it seemed inconceivable to them that a young woman, a student just like them, could live in a hotel. It wasn’t even a particularly fancy hotel. On the contrary, it was one of those ever-sprawling American chains; but the mere sentence She lives in a hotel was provocative, explosive. An eighteen-year-old girl in an American hotel. Everyone thought she would become a writer, everyone except for her; it was her mother who was the writer, and the fact that her mother had been dead a long time didn’t change a thing. The writer meant her mother. And she, Amelia Dehr, was a character, and, as far as they could tell, determined to remain one. And whether she was the author who dreamed up that character, or merely a character in someone else’s story, nobody could quite say, and the question was never answered.

hotel nights

1

Paul couldn’t believe that she lived in a hotel. Better yet, or worse, he had known it, then forgotten. They talked about her on campus, rumours had preceded her, so much that her body already existed in whispers, but Paul didn’t care about gossip. He cared about girls, and women. Their mouths, their flesh. He was eighteen years old, and living multiple lives. By day he went to university, he stared at huge blackboards or whiteboards, he traded and compared notes with his classmates; it was odd how sometimes they would swear they couldn’t possibly have gone to the same lecture, until they landed on one or two identical sentences and had to concede that they had indeed both been listening to the same professor, but aside from those fixed points each of their notebooks meandered, diverged. The ones who understood best were the ones who understood nothing and, terrified by their own ignorance, had written everything down verbatim.

They spent hours gathered together at the café: girls running their fingers over his scalp and stroking it, cold fingers probing the waves of his hair, exploring the topography of his cranium, light fingers slipping across the back of his head as if momentarily, unwittingly breathing life into long-forgotten theories, as if the bumps they found could reveal the secrets of his personality or his soul through the old, discredited markers of amativeness or acquisitiveness, or benevolence, or adhesiveness – even though the mystery these eighteen-year-old girls ever so gently touching his head were trying to decipher was simply that of their own desire, the desire they felt for this young man in particular or the desire they felt for young men in general. All these fresh-faced students were happy; they talked too much, their breaths forming small clouds in the cold air, they smoked too much, drank coffee in quantities that set their hearts racing. Deep down, they scared as easily as deer, even the boys, especially the boys, and so they shied away from open contact – would never have dared to lock hands, much less lock lips. Yet they were all so close together that just one of them had to catch a cold for all the others to catch it as well.

In the evenings, at night, there were long, drunken, anonymous parties where Paul lost his friends in the crowd, intentionally lost them, because everybody swooned over him with his swimmer’s torso and his long lashes. Nights when people handed him glasses full of clear or cloudy liquids that sometimes plunged him into extraordinary slowness where everything flowed as if underwater and where gestures were never quite completed, where they barely got nine-tenths of the way through. Nights on rooftops or in basements or at mansions or in abandoned métro stations. Nights full of smoke. Nights when he lost sight of his friends then found them again, but sometimes it wasn’t them, sometimes it was just his face, just his own reflection caught here or there. Nights when people tried in vain to get him into bed. Nights when he was obsessed with sex because at that time Paul was under a curse or a spell, he just couldn’t get rid of his virginity, every time, the girl disappeared or he left or someone showed up or they had to go; but stranger still, even when he had sex, and whatever the definition one gave the act, whether it was ordinary or pornographic or legal or none of the above, even when he inserted his genitals into someone else’s, even when he came with an uncontrollable shudder and the deed had finally been done, he thought, finally! – the next day or a few days later, it was as if nothing had happened. He was a virgin again, and resigned to it. It was a nightmare for him.

He slept little but slept well. Wherever he was, at the university or at the café, in an unknown house or at home, most of the time, just a few feet away would be a screen with flickering images of m

urders and investigations or funerals and tears or collapses and escapes or questions and answers, or only questions. And he, impervious to all these tragedies, slept peacefully. But that was before Amelia Dehr. That was before the hotel.

There wasn’t much money. His father had been blunt: the classes were fine, the rest wasn’t. He took the first job that came his way, distractedly, without even realising what he was agreeing to; indifferent or inattentive, because what he cared about was beginning a new life. Security monitoring – or rather, simply monitoring – during the off-hours at the hotel. In the evening; at night. He got bored there. And he offset that boredom by watching the women. Watching them at a remove. He looked for them. Sometimes he found them, sometimes he lost them. In any case, it was a game he played without any of them knowing. This one leaving her room and immediately disappearing, vanishing. Only to reappear, somewhere he hadn’t expected, as if by magic, slipping from one small window to another, almost at random. There were nine cameras and just as many squares on the monitoring screen, Paul’s screen. He waited for surprises; he could only anticipate their trajectories to a certain degree, because that didn’t account for random stops, sudden about-faces. He stared at all those bodies walking around and thinking thoughts he couldn’t see on the screens. He couldn’t see what had been forgotten in the rooms, on the nightstands, in the bathrooms; and he had no hope of seeing any lingering afterthoughts. And every so often came one of Paul’s favourite moments: rare, unexpected, evasive embraces in the emergency stairwells. All he ever saw was a fire door slowly – lazily – closing.

He couldn’t really say that he enjoyed his job, which he didn’t think of as a job so much as an accident – less than that in fact, an incident, nothing more: a casual thing. But he could say that he enjoyed watching women. That he enjoyed looking down at them, playing at (or so he told himself ) looking down on them – and only at the hotel, only at night, was that possible for him, specifically because of the cameras, aimed so sharply downward that he was positioned high up, like the sun, like some god. If the warmer air – the sighs they exhaled as they redid their make-up in the elevator’s infinite mirrors, the seismic heat their warm flesh exuded as they stood in these empty, thoroughly ventilated spaces – and these exhalations rising up, accumulating beneath the ceiling, could see, then that vapour’s gaze would be the gaze Paul now had. So dreamed Paul.

When the women weren’t going in and out much any more or he wasn’t watching them much any more, he tried to study. He liked university but more than that he liked being a student, it exhilarated him, as did the pride his father felt – which didn’t keep him from being, deep down, a bit jealous of Paul, just a bit, in those little crannies of his heart of which he himself was unaware – actively, insistently unaware, in total denial. He would rather cut off his arm than admit it, because he was a good man, as proud of his goodwill as he was of his son, and a good man doesn’t envy his only child. But, at the construction site, he sometimes thought of that university and spat in the drywall, and sometimes pissed in the drywall, as people have always done – general hygiene notwithstanding – to bind the components, to (this Paul knew, even if his father didn’t) alter the pH, the acidity, the stability; and to (this his father knew, even if Paul didn’t) leave something of oneself in someone else’s space, in walls that construction workers laboured to build with no hope of ever living there. To secretly, silently spit or piss on other people’s comfort.

Their origins were modest and they took nothing for granted, especially not university education; they lived, had lived, Paul thought, as if nothing under their feet was certain. As if they were on water – but that image didn’t occur to him then; he would only think it much later, after finally meeting Amelia Dehr.

He tried to study but needed to take in far more than just his architecture classes, which sectioned off various eras, areas, and approaches. He had cut off – or so he thought – all contact with his past, which he didn’t think of as a past so much as an incident, more than that, an accident. The first eighteen years of his life had given him a particular body, and this body had a particular relationship with space, with others. He sensed that he didn’t quite belong. At the outset, he had observed. And imitated. First the clothes, which he stole. Then the haircut, which he’d had to adopt a whole new language just to describe, to ask for. It was a challenge he had never faced before, as complex as an international expedition, the greatest of conquests. Finally, he mastered the delicate art of talking. But this drained him. Some nights in the dorms he stayed in his bedroom, in the dark. Listening to the noises in the hallway, and all the other students’ chatter made him seasick; and if someone knocked on his door, he wouldn’t answer, the idea that it might be a mistake horrifying him just as much as the idea that it might not. He was terrified that it would never end and, even though it never did quite fade away, not really, still it only lasted two weeks, maybe three, and then it didn’t matter any more. He was already feeling at home, or so he thought. He had closer friends than ever, whom he loved intensely, for whom he sometimes thought he would have given an arm, a kidney, even. But sometimes he forgot their names. Or their faces. At three or four in the morning he would realise that all he retained of this friend, this guy or girl, was just a blurry shape. And sometimes it was just his face, just his own reflection caught here or there. Maybe deep down some part of him still lived in darkness. And maybe, worse still, he had gone on to think of this darkness, in bleak terms – all the bleaker given that he was an eighteen-year-old man with a swimmer’s torso, with long lashes, who now had a new self – as real life.

*

For some people, the Elisse hotel seemed to be not just where but how crimes were committed. It was the kind of place that stood in for reality, if reality was, first and foremost, disappointing. It was, in any case, no place for lovers of literature or even plot. Some member of an older generation might end up there on occasion, and Paul didn’t even try to disguise how he stared at them as worry and sometimes, rarely, death took root in their souls the same (thankfully) brief way they settled in a bedroom exactly like all the others for the night. It was a place that killed not by beauty or ugliness but, really, by indifference. Somehow, this no-man’s-land quality accounted for the chain’s immediate success: it was exactly what people were looking for here when they had some choice of here. It boasted every modern comfort, and the secret to this comfort was its neutrality, its anonymity. Nothing was more like an Elisse hotel than another Elisse hotel and so it was almost possible for someone staying there to wake up as someone else. Or, better still, as no one at all. Yes, in these mid-range spots it was possible to be oneself and someone else, oneself and no one at all. The windows were perfectly square and did not open; the air conditioning circulated microbes and distributed them equitably. All these forms of contagion mixed together. People were so scarcely themselves there that the coughs they coughed were those of strangers. Paul was bored stiff, and after enough time had gone by, gently swivelling his chair in front of the surveillance video screens, all alone in an empty lobby, some sort of trance came over him. The fountain’s unceasing flow did not help. He wasn’t lonely so much as he was feeling the cumulative effect of certain physical phenomena; not so much a state as an environment, like certain altitudes or depths, and eventually he started breathing differently, in a new rhythm. Sometimes his ears buzzed. He waited for something to happen and sometimes, out of sheer isolation, something did, just not in the way he hoped.

For two or three hours, the usual clientele for this type of establishment would come and go: young and not-so-young executives, individuals passing through, here for a function or a mission, for union committees or academic colloquia. Some, oddly enough, seemed to have taken a shine to the place. Paul didn’t care about them, and they cared even less about Paul. This didn’t keep them from polite conversations or the occasional joke, but the moment they turned away, smiles faded from faces and faces faded from memory. Some nights there w

as a dead calm: nobody walked past for hours on end, Paul’s heel swivelled the chair left and right unthinkingly, no human sound rose above the flowing water which created what the hotel’s architects designated a climate – on those nights, something did happen. Paul didn’t realise it because he was waiting for something to happen in front of him, something he might see with his own eyes. Something outside him. What did happen, however, took place inside him. He sat amongst the monitor screens displaying empty elevators and deserted hallways and the television channel playing the news bulletin on a loop, and time went by, always slower than he liked, and suddenly, at the pinnacle of his boredom, something would happen. The sliding doors, for example, might sigh open, activated by the movement of a body nowhere to be seen. Or someone might walk past one of the nine monitor screens. Or, very specifically, he might suddenly insist that he could see a woman sitting, her hair damp, on the edge of the fountain where she’s just washed her hair. He knows she’s there, just as he knows the door’s just opened and someone’s entered – he’d swear on it, it’s a fact, an indisputable fact – until he looks up. The water dripping from her hair onto her shirt seems to darken her hair and her clothes, her eyes meet his, she takes her time, he does as well. In that moment he could almost foresee exactly where her eyes would be. But he’d look up and, sure enough, see nobody there.

Paul dismissed these impressions as if they were figments of his imagination, the effects of exhaustion, the artificial light. He didn’t think of these moments, these mistakes, as events. He waited. He waited but, one night after the doors were locked – in the wee hours, guests buzzed at the door to be let in – he saw Amelia Dehr on his monitor screen, standing in the street like an apparition, and he panicked. He had never imagined that he might see her there, at two or three in the morning, at the place where he worked.

Night as It Falls

Night as It Falls